Hi all,

Today I wanted to provide some information that will help you get the most out of Foglight's .NET monitoring. This article will be mainly conceptual in nature. I'll be following up with a second article that provides more practical hands-on guidance for using these concepts in Foglight's .NET agent configurations.

Foglight's .NET agent has a set of detailed tunings available in its desktop management console (which you may see listed in the Windows Start menu as the Intercept Studio or Intercept Management Console) that allow for configurations concerning Entry Points, Namespaces, and Resources. This article gives an overview of these concepts as they apply to .NET applications and will set the stage for our follow-on discussions.

Note that this article will assume that you have a basic understanding of .NET assemblies. They are an important concept that describe the physical organization of code modules in .NET, and the Intercept Management Console lets you browse assembly modules in order to use their components when configuring the .NET agent.

Namespaces

In Microsoft's .NET, namespaces are a fundamental unit of logical code grouping. Namespaces are not a replacement for assemblies, but an additional organizational technique that complements assemblies. Namespaces are a way of grouping type names and reducing the chance of name collisions. A namespace can contain both other namespaces and types. The full name of a type includes the combination of namespaces that contain that type.

The Namespace Hierarchy and Fully-Qualified Names

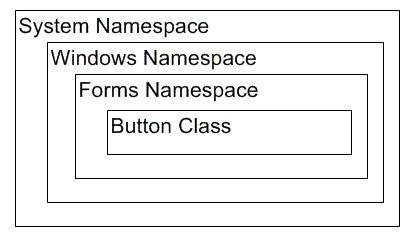

Here's a quick example from the .NET class library. As shown below, the Button type is contained in the System.Windows.Forms namespace. That's actually shorthand for the situation shown below, which shows that the Button class is contained in the Forms namespace that is contained in the Windows namespace that is contained in the root System namespace:

The namespace hierarchy helps distinguish types with the same name from one another - .NET developers use the Namespace statement to declare namespace hierarchies in their code. By default, a .NET project declares a root namespace that has the same name as the project. For example, you might define your own class named Button, but it might be contained in the ControlPanel namespace within the PowerPlant namespace. If the declaration was in a project called PowerLib, then the fully qualified name of the Button class would be PowerLib.PowerPlant.ControlPanel.Button.

Foglight's .NET agent comes preconfigured with a set of default namespaces which you can customize if needed using the Intercept Studio. Namespaces may be added to the default list and be treated as either Entry Points or as Resources.

Entry Points and Resources

Foglight for .Net monitors performance at two levels:

1) Entry Points - the execution time of a web page or entry points of an executable application (these are the top level functions that you would see in the Action column of Foglight's .NET Requests dashboard) and

2) Resources - the execution time of calls made from Entry Points - these are the calls which appear within the Execution Tree of a trace on a given Entry Point. Note that if an Entry Point that appears in the .NET Requests dashboard makes calls to Resources in specific namespaces, you will not see the complete execution tree for that Entry Point unless you either:

a) specify those Resources as custom Resources to monitor, or

b) tell the agent to monitor all namespaces. Note that setting the agent to monitor all namespaces may exact a level of overhead that is not desirable in production environments.

By default, Foglight's .NET agent is set to capture performance traces for Entry Points whose execution time exceeds 5000 ms (this is called the Alerting Threshold in the agent documentation). Enabling a Namespace or class as an Entry Point will cause a new event to be generated the first time the Namespace is encountered if the threshold is crossed. The cartridge comes pre-configured with a list of well-known Entry Points but you can certainly add your own (along with custom overrides for the Alerting Threshold). Using the Intercept Studio, you can add your own Entry Points as either ASP.NET pages, ASP.NET MVC pages, Web Service calls, or Custom Functions.

Monitoring Functions as Resources

A function that is enabled for monitoring as a Resource will be included in the execution tree when it is called by an Entry Point, even if monitor all namespaces monitoring is not enabled. In other words, the Resource mechanism lets you choose specific code that should be traced so that you can establish a lower level of overhead while maximizing the diagnostic depth you need. .NET code traced as a Resource will provide both execution time and local variable information. The execution time threshold setting for Resource calls is called the Sensitivity Threshold in the agent documentation.

Using the Intercept Studio, you can specify custom resources with customized overrides to the Sensitivity Thresholds.

An Example

Here's a brief example that will help tie this together.

As we said, enabling a Namespace or class as an Entry Point will cause a new event to be generated the first time the Namespace is encountered if the Alerting Threshold is crossed. Otherwise, information for that Namespace or class will be included in the event for a parent Entry Point if there is one. For example, let's say the default Alerting Threshold is set to 5000 ms, the MyCompany Namespace has been added as an Entry Point, and the following sequence of calls is made:

|

Call |

Execution Time |

|

15,000 |

|

14,000 |

|

12,000 |

|

2,000 |

|

1,000 |

We're assuming that MethodA() is the first MyCompany method that the Foglight .NET agent sees. By enabling MyCompany as an Entry Point, MethodA() will be reported as a separate event (i.e. a top level entry in the Foglight .NET Requests dashboard). The remaining methods will be collected as Resource calls in the MethodA() Execution Tree if one of the following is true:

a) the agent has been told to Monitor All Namespaces, or

b) MethodB(), MethodC(), MethodD(), etc, have been specifically configured as Resources

Note that if MethodB(), MethodC(), and MethodD() were configured as Entry Points, rather than as Resources, then top level entries in the .NET Requests dashboard would be seen for both MethodA() and MethodB(), but not for MethodC() or MethodD() since their execution times fall below the default Alerting Threshold. Also, the Execution Tree for MethodA() would stop at MethodB(), whose aggregated execution time would be shown. In addition, you'd see the aggregated execution time for MethodB() and its children listed as Internal Execution Time (see the next section).

Internal Execution Time

In the .NET dashboard's drilldowns for performance traces, you may see portions of an Entry Point's execution time allocated to 'Internal Execution Time'. This refers to execution time not related to the currently instrumented set of resource calls. This may occur under circumstances where the ability to trace the call has been interrupted - examples of this can be a transition into obfuscated code, calls into code whose namespaces are not configured monitoring, or calls into non-.NET modules (i.e. calls into unmanaged code).

Methods to mitigate the amount of internal execution time include:

a) Directing the agent to monitor all websites by default

b) enabling namespaces for monitoring that have been disabled where the call tree includes those namespaces, and

c) if possible, minimizing the use of obfuscated code

Big thanks to my colleague Keith O'Leary who generated much of the content I've presented here. I hope you found this useful. Stay tuned for Part 2 coming to a blog entry near you.

Robert Statsinger